When Starry Night Has Been Painted a Thousand Times, Is It Still Art?

16/01/2026

Hector Chan

Dafencun, Shenzhen, China

Have you ever wondered where copies of Vincent van Gogh come from?

Here, you can buy a small Van Gogh for ten dollars. A surprisingly decent, life-size one for thirty. And if you want a Starry Night large enough to cover an entire wall—no problem. They have that too.

This is Dafen Oil Painting Village, home to over 1200 galleries.

Before visiting, I had heard all the legends. Entire families painting reproductions for a living. Masterpieces sold for the price of lunch. Paintings quietly exported to hotels, offices, and living rooms across Europe and the U.S. Walking through the village, you realise most of this sagas is true. Dafen is not large—roughly eight blocks in each direction—but it is dense with production. Small studios spill into the street. Paintings lean against walls, dry in stacks, or are carried out fresh from the easel. Art is not displayed reverently here; it circulates.

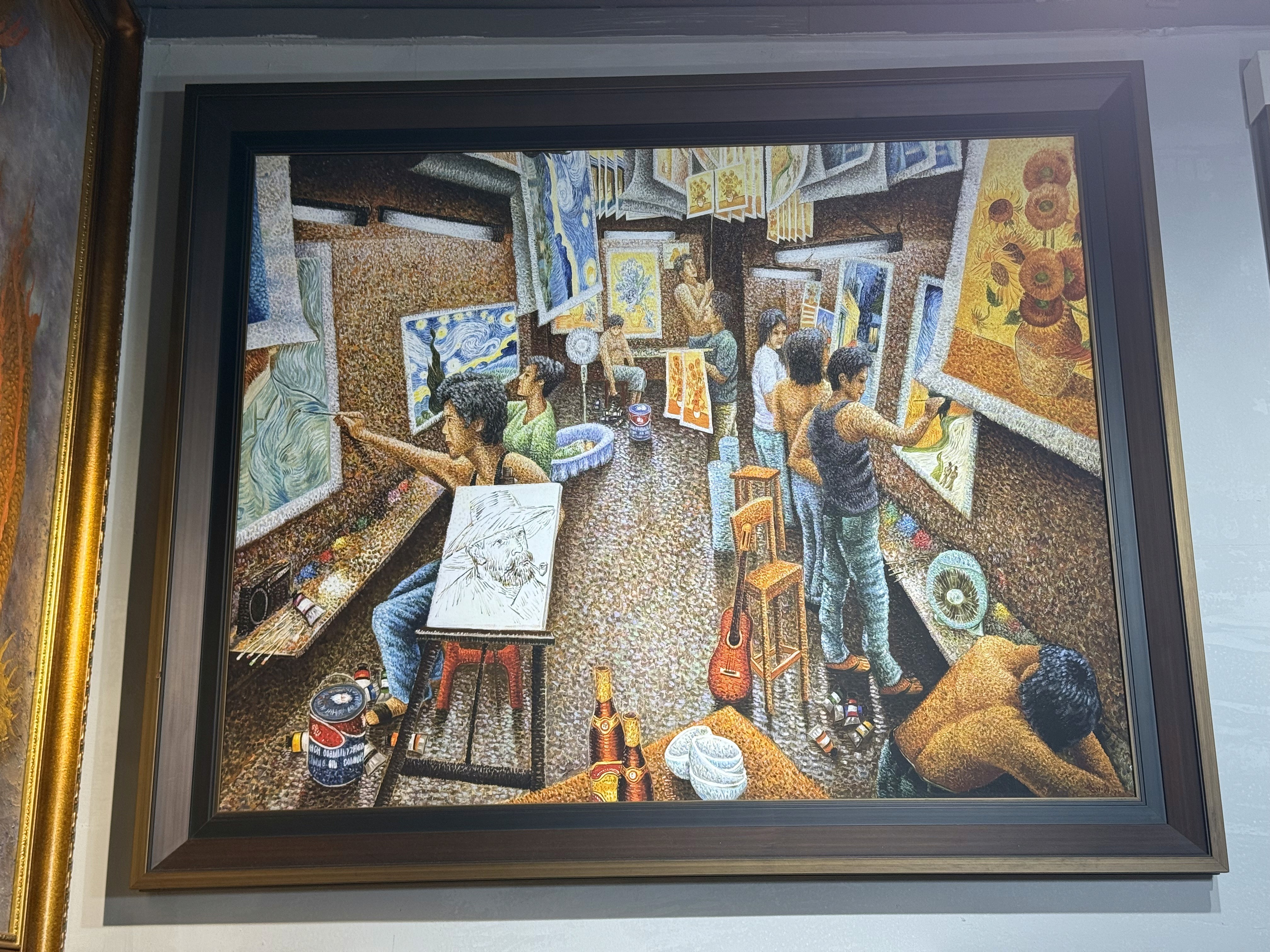

Snapshots of Dafen Village, notice how a brand new sunflower is being painted on the right side.

Van Gogh's paintings remain the most popular genre.

So the question sharpens: is art still art once it has been repeated this many times? Is repetition itself a form of mastery—or does it eventually empty meaning from the image altogether? Almost none of the painters here have seen the original works. Yet in a system governed entirely by demand, that distinction barely matters. What is real and what is copied collapses under the pressure of profit. This is art stripped to its most transactional form: images produced not because they are believed in, but because they sell.

This is, in many ways, the art market at its most honest. There is no pretense of inspiration or authorship. The only question that matters is what name can be attached—after—Van Gogh, Monet, whoever moves fastest. A life-size painting can be bought here for a fraction of what the same image, reframed and recontextualized, would command in the West. Value is no longer located in paint, surface, or experience, but in branding and distance.

I realised, toward the end of my visit, that I couldn’t stay much longer. After seeing a hundred versions of Starry Night, I needed to step outside. Otherwise, I feared I would forget the depth of the color, the weight of the paint, and the quiet deliberateness behind what often appears spontaneous in Vincent van Gogh’s work. That—precisely there—is where his mastery lies. And perhaps that is Dafen’s quiet lesson: when art becomes pure repetition, it does not disappear—but it reminds us exactly what we risk losing.

A Albert Bierstadt copy, notice a copy of Impression, Sunrise, on the right.

当《星空》被画了一千次,它还是艺术吗?

你有没有想过,那些遍布世界各地的梵高复制画,究竟是从哪里来的?

在这里,你可以用十美元买到一张小尺寸的“梵高”;三十美元,就能带走一张尺寸相当、完成度不错的版本;如果你想要一张大到可以铺满整面墙的《星空》,也完全没问题——这里应有尽有。

这里是 大芬油画村。

在来之前,我听过无数关于这里的传说:整整几代人以复制世界名画为生;一张画的价格和一顿午餐差不多;这些作品被源源不断地出口到欧美,进入酒店、办公室,甚至某些“看起来很像博物馆”的空间。真正走进大芬之后,你会发现,这些传说大多都是真的。

大芬并不大,大概也就八个街区见方,却异常密集。保守估计,这里至少有一百五十家小画廊——很多其实就是一两间房,由一到两位画家经营。这些空间既是工作室,也是展示间,更是直接交易的场所。你能看到一张《向日葵》刚画完放在地上晾干,旁边另一张已经被买走,等着打包出货。艺术在这里不是被“展示”的,而是被不断地流通。

There are some very self made good artists as well. This artist here specialises in painting photo like portraits.

画的题材几乎什么都有,但失衡非常明显。欧洲绘画占据了绝对主导地位。偶尔能看到文艺复兴时期的圣母像,但真正统治街道的,还是印象派。梵高和莫奈几乎无处不在,荷兰黄金时代的静物画也稳定出镜。与此同时,也能看到中国水墨,以及大量被直接称为“装饰画”的作品——为酒店、餐厅和商业空间量身定做的、尺寸大、情绪安全、不会惹麻烦的画。

真正有意思的,并不是“种类多”,而是“品味的稳定性”。当代艺术世界已经变了这么多,但印象派图像依然是最容易被复制、最容易被识别、也最容易被卖掉的那一类。它们之所以存在,不是因为被理解,而是因为好卖。

严格来说,这些画并不算“伪造”。没人试图把它们做旧,也没人假装它们来自十九世纪。所有作品看起来都很新——因为它们确实就是刚画出来的。颜色通常偏亮,笔触略显用力。绝大多数画家从未亲眼见过原作,只有极少数人看过。由于我自己看过不少梵高的真迹,我可以很确定地说:这里看到的大部分作品,其实并不像梵高。从拍卖行的归类角度来看,它们顶多算是“仿某某风格”或“某某的追随者”。但话说回来,当你用不到五十美元买到一张“全尺寸名作”的时候,似乎也很难再苛责什么。

This painting by artist Zhao Xiaoyong is portraying his entire family copying Van Goghs. Business has not been great lately and many members has since switched career paths.

真正让我着迷的,不是质量,而是动机。

我年轻时学画,也大量临摹过名作——这和法国学院派的训练方式并没有本质区别:通过复制去理解技法、结构和用色,然后慢慢形成自己的语言。复制是一种手段,而不是终点。但在大芬,复制本身就是目的。当我问画家们,为什么画梵高,答案异常直接:因为他卖得最好。有一位画家告诉我,她画《向日葵》已经完全不需要参考图了,因为她画过“成千上万张”。在这里,技术通过重复被打磨到极致,而作者性却被一点点抹去。艺术变成了劳动,记忆变成了肌肉反应。

当然,如今的大芬也在努力讲述一个新的故事:艺术博物馆、驻留项目、政府补贴住房、技能竞赛、原创艺术的孵化空间……这一切都是真实存在的,也并非空洞的宣传。你能感受到一种转型的野心。但当你真正走进那些工作室时,也很难忽视支撑整个生态系统的核心逻辑:高度效率化的复制,精准对接全球市场的需求。

于是,一个问题不可避免地浮现出来:艺术,在被重复了这么多次之后,还是艺术吗?

当重复达到这种程度,它究竟是一种熟练,还是对意义的持续消耗?几乎没有人见过原作,但在一个完全由利润驱动的体系里,这已经不重要了。什么是真,什么是假,在这里并不构成道德困扰。重要的只有速度、价格,以及名字——after 梵高,after 莫奈。你可以在这里用极低的价格,买到一张与西方市场中高价流通的“同一图像”。价值不再存在于颜料、表面或经验之中,而存在于品牌、语境,以及距离本身。

走到后来,我发现自己不能再待下去了。看完一百张不同版本的《星空》之后,我必须走到外面去。否则,我担心自己会忘记真正的梵高:颜色的深度,颜料的重量,以及那些看似疯狂、实则极其克制的笔触选择。文森特·梵高的真正大师之处,恰恰就在这里。

也许,大芬真正教会我们的,并不是“什么不是艺术”,而是:当艺术被彻底压缩为可复制、可定价、可批量生产的图像时,我们究竟在失去什么。

© 2025 by Hector Chen